A look into the use of sustainability and impact labels for financial products by investors in Europe and the USA.

At Nordic Sustainability we have followed investors making bold claims about their products’ sustainability impacts. We were curious to find out how comfortable investors actually are with their product claims, especially in light of ESMA’s new guidelines for sustainability-related fund labels. This white paper outlines findings from our explorative survey, our reflections on related trends and developments, and a set of useful tips for navigating the tricky world of impact investing.

A survey to understand impact investing and aspirations

The financial landscape has reached a turning point. Investing ‘responsibly’ by mitigating negative impacts and excluding ‘sin’ industries is no longer enough. Investors are increasingly looking to make a positive impact through the capital they allocate, alongside financial returns. They have thus turned to impact investing – a market which was valued at $3 trillion in 2023 and is expected to reach over $7 trillion by the end of 2033.

In the context of rising interest in impact investing, and the introduction of numerous new regulatory and disclosure requirements, we have noticed a feeling of uncertainty among our clients about how to truly claim impact and credibly communicate such efforts.

At Nordic Sustainability we find it crucial to understand the most pressings issues faced by financial institutions (FIs) to better pinpoint the specific needs we should address in our work as consultants. Excited about the potential of impact investing as the new frontier in finance, we conducted a survey of 20 financial institutions across Europe and the United States.

The aim of this survey was to investigate both the current market situation and investors’ aspirations for impact investing. We partnered with Fin International, a UK-based communications agency specialised in investment management, to get to the crux of the issues at hand.

What it takes to be an impact investor

Before we jump into the survey’s findings, we want to clarify what we mean by impact investing. While it is becoming increasingly standardised, the conversation regarding impact and sustainable investing is still situated in a complex ecosystem of – at times conflicting – regulations and definitions.

Two important initiatives to highlight are:

1. The Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) introduced the widely accepted definition of impact investments, as intentional, measurable, and evidence based. Other requirements include developing a clear Theory of Change to inform portfolio construction and management, and data to prove the impact.

2. The European Securities and Markets Authority’s (ESMA)released guidance on fund names in May 2024. These lay out specific requirements, including investment thresholds and exclusion criteria, for investors using ESG and sustainability terms to label and market funds, including impact and sustainable funds.

While new guidelines make the formerly murky waters clearer to navigate and the impact and sustainability criteria for investments are now more defined, making sure institutions have the right KPIs and evidence to prove impact remains a challenge.

Key trends identified by the survey

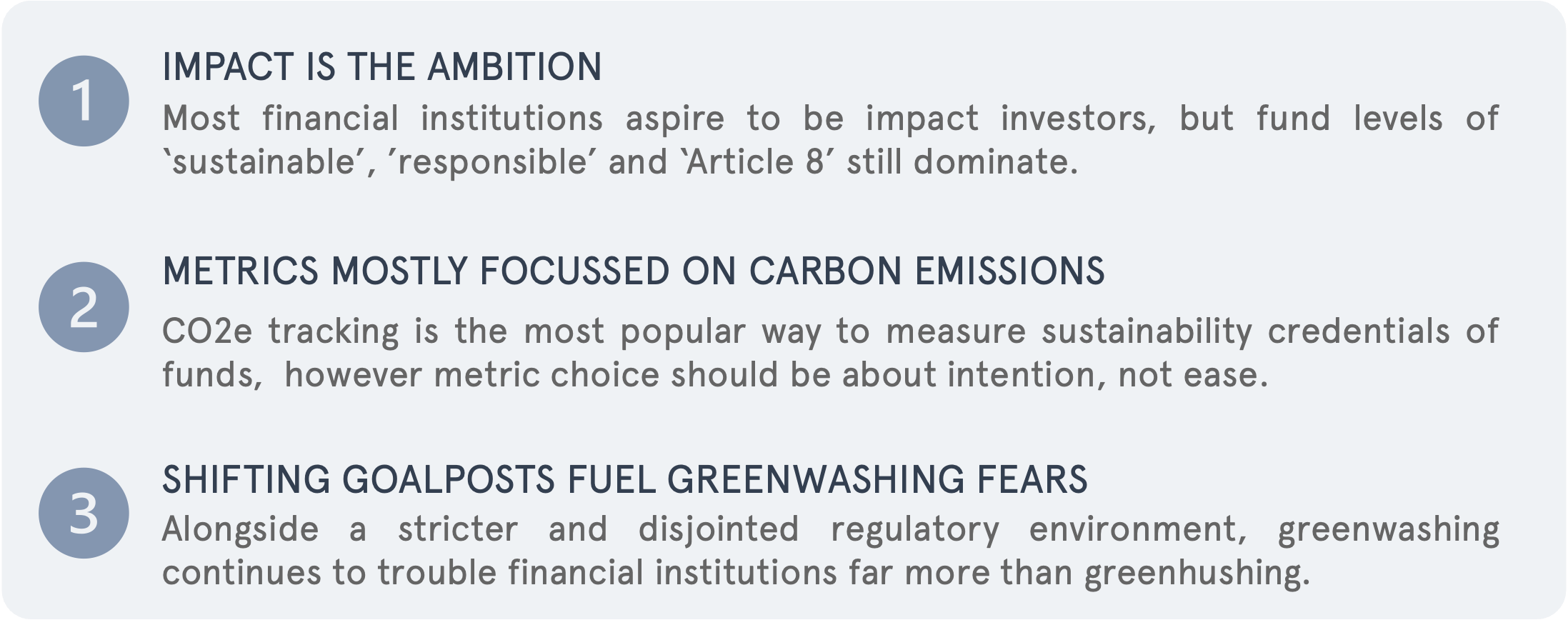

1. Impact is the ambition

Most financial institutions aspire to be impact investors, but fund levels of ‘sustainable’, ’responsible’ and ‘Article 8’ still dominate.

Perceived added value

68% of surveyed investors want to be able to claim impact, indicating that impact investing is an aspiration for many investors. Labelling products in this way appears to create additional value to investors, with 80% of respondents stating that investor relations have been positively impacted by sustainability and 75% wanting to use it as a brand differentiator.

Drivers to do good

We put this trend down to a growing desire among investors to ‘do good’ and a perceived need to invest responsibly. Investing has always been more than a calculative endeavour, it involves decision-making influenced by personality traits, behavioural factors, company-specific factors etc.Impact investing can be considered a natural consequence of society becoming more impact aware. In connection to this, climate scenario models are maturing and outline major financial risks to business such as nature loss and extreme weather conditions. The potential shocks to the market are also playing a role in investors taking a more environmentally and impact aware stance.

Easier said than done

Whilst we are happy to see the desire to become impact investors, we recommend investors proceed with caution. The difference between sustainability and impact investing is the intent to create specific and additional positive impact.

2. Metrics mostly focussed on carbon emissions

CO2e tracking is the most popular way to measure sustainability credentials of funds, however metric choice should be about intention, not ease.

Slowly moving beyond carbon metrics

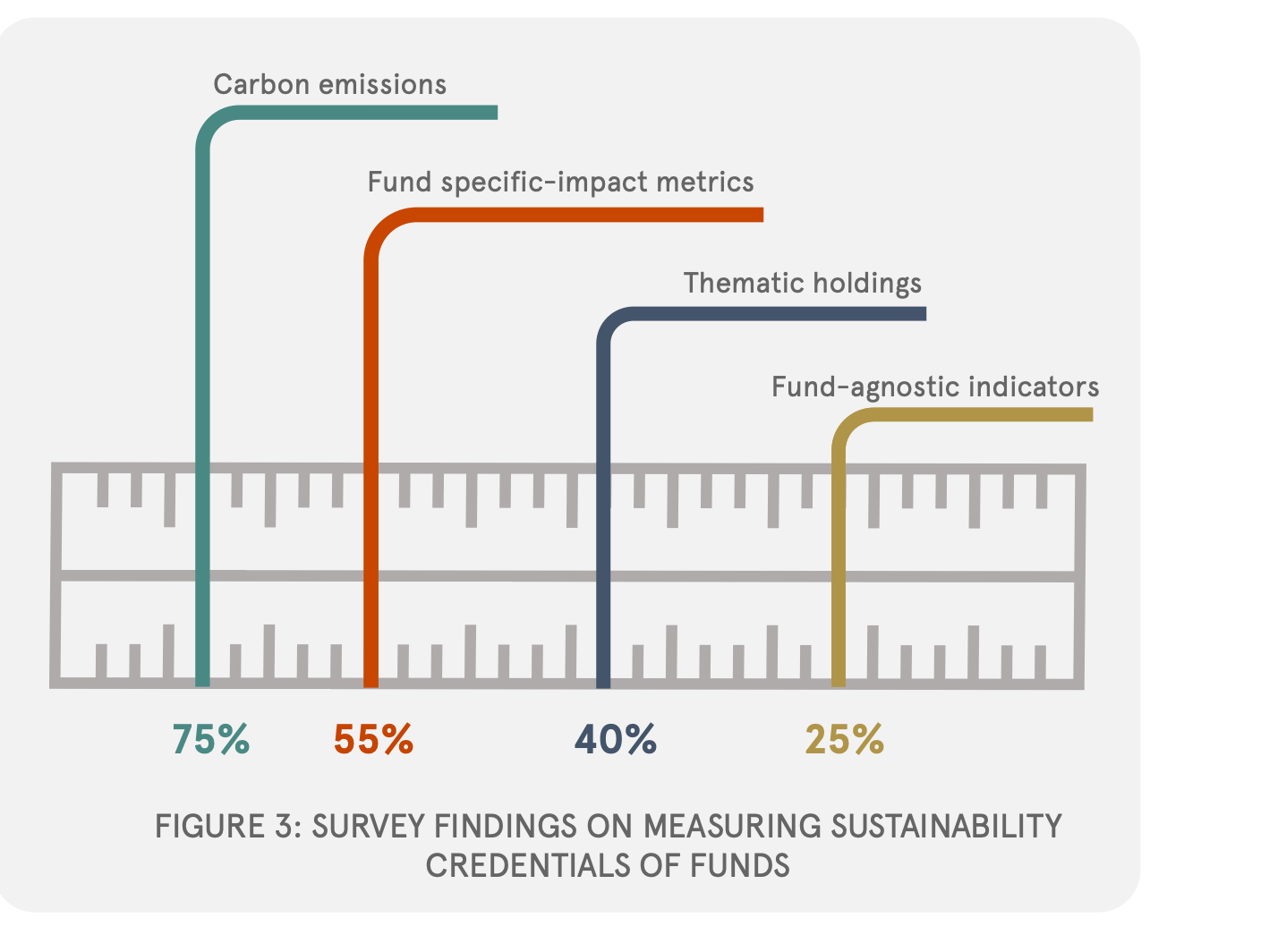

The survey findings show carbon emissions are the most used metric for measuring funds’ sustainability credentials, 75% of respondents said they use this to substantiate their claims. Surprisingly, 3 of the 8 respondents who said they use the ‘impact’ label, said they do not yet measure fund-specific impact metrics.

We think the metric’s popularity makes sense: climate has long dominated both the EU regulatory landscape and sustainable finance space. Climate change mitigation and adaptation are the most comprehensive of the six environmental objectives under the EU Taxonomy, and while there is a growing appetite for investments in nature and biodiversity, investors are faced with the challenge of numerous and complicated metrics lacking the straightforward appeal of CO2e.

Importance of measurability

The newly published ESMA guidelines on fund names further enforce this climate focus. Under these, funds using impact-related terms should follow PAB exclusion criteria which restrict investments in fossil fuels, as well as controversial weapons, tobacco and global norms violations. The guidelines also stress that impact funds need to ensure that investments generate a measurable positive environmental or social impact.

At Nordic Sustainability, we understand the challenge of moving beyond CO2e but see the importance of organisations being as specific, e.g. at topic or sector level, as possible in their metrics to start collecting the data and evidence required for impact investing.

3. Shifting goalposts fuel greenwashing fears

Alongside a stricter and disjointed regulatory environment, greenwashing continues to trouble financial institutions far more than greenhushing.

Investors are confident in sustainability claims yet fearful of greenwashing

Despite 70% of survey respondents believing that their sustainability claims and messaging are clear and accurate at both product and brand level, a fear of greenwashing persists. Although only 15% expressed concern at overstating their sustainability credentials, 53% of investors saw greenwashing as their biggest concern. This goes for the breadth of sustainability labels not just impact.

What causes this contradictory feeling between fear of greenwashing on the one hand and confidence in the accuracy of sustainability claims on the other? It likely stems from a disjointed regulatory landscape, in which the goalpost keeps shifting as definitions of key sustainable finance concepts change. The new ESMA guidelines are a case in point: 49% of Article 8 funds with environmental or impact-related terms may need to change their names or divest due to breaches of the PAB exclusion criteria.

Standardisation challenges and a clear need for transparency

The issue of a moving goalpost is especially pertinent for impact investing given its more subjective nature. It has been widely debated that impact investing cannot be standardised and should be more ‘norms based’ to grant the investor flexibility to choose their own objective.2 However, this needs to be balanced with transparency.

Closing remarks

The survey results leave us excited about investors’ ambition levels and desire to create a real-world positive impact, mixed with some reservations about the ability to achieve this. Let’s not forget we are talking about an investment universe of real-world companies whose primary aim is still to make a profit, and the actual number of companies making a purely positive impact is sadly still relatively small.

Take as an example a company owning and operating windfarms. Yes, there is a measurable and evidence-based positive climate impact in the immediate renewable energy production. However, purely focusing on this ignores the potentially harmful impact on local biodiversity of these wind farms, the energy-intensive nature of steel production, and the lack of recyclability of main components. If done properly, the company in question needs to address their wider negative effects to claim pure positive impact.

This being said, the more demand there is for these financial products , the better, as the more investors aim for impact, the closer we will get to where we need to be.

Here is a summary of our three top tips from our experience with impact investing: