The shared mental models underpinning our approach to corporate sustainability are changing argues Felix, Manager at Nordic Sustainability. The new European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), he suggests, call into question a tradition of misguided materiality assessments – and pave the way for a more transformative understanding of corporate sustainability.

Mental models are deeply ingrained cultural ways of understanding and making sense of the world around us. They provide meaning and structure to complex and messy situations, but because they are largely unquestioned, they can contribute to systemic problems. One example of a common mental model is the belief that “I am what I do,” which drives many conversations between strangers. However, this model can also lead to the entrenchment of problematic ideas, such as the idea that one’s job should be the sole source of happiness and meaning.

In the context of modern corporations, another mental model has influenced how businesses are governed, with stakeholders’ and shareholders’ interests being perceived as the ultimate concern. Felix, Manager at Nordic Sustainability, argues that this mental model has shaped the concept of materiality in particular, leading to the idea that ‘what’s not perceived to matter, doesn’t matter’. This is reflected in economic models such as perfect information in consumer decision-making, which is unrealistic, and macroeconomics that ignores finite physical resources in favor of perceived pricing signals.

In the corporate sustainability profession, I argue that we are currently able to witness a key mental model being redefined entirely. This mental model underpins our understanding of corporate sustainability, and potentially of the systemic value of business as such. I suggest it can be summarised as “What’s not perceived to matter, doesn’t matter”.

From perception- to fact-based materiality

Materiality has been a part of the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) for a very long time. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) first addressed the concept of materiality in 1933 the central idea behind materiality was that investors do not want to be buried with meaningless information irrelevant to their decision of whether to invest in a specific business1. Instead, the materiality principle is supposed to act as a disclosure threshold – what’s not important to the investor’s decision shouldn’t be reported.

As our global economy continued to grow, and with it corporate scandals and environmental destruction, this concept of materiality was broadened significantly in two strides. Firstly, as it became obvious for many businesses that ethical misconduct, human rights violations and destruction of ecosystems are generally not helpful for the bottom line, the concept of financial materiality emphasized that “non-financial information” has a sizeable impact on a company’s financial performance. In the context of corporate sustainability specifically, that means that a company should disclose its practices around managing “Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) risks” – for example, how prepared it is for the transition to a low-carbon economy. Secondly, the concept of impact materiality was introduced to shed light on the fact that even though a company’s financials may not be impacted by a certain issue, it certainly matters to affected stakeholders when they are impacted – for example, garment workers in the textile supply chain being paid less than local living wages.

For years, organisations like the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) advocated for materiality assessments to combine these two perspectives into a double materiality approach as a best practice. Yet, the methodology that companies used to determine double materiality was exclusively based on perception – in line with the mental model of “What’s not perceived to matter, doesn’t matter” and companies’ lack of effort to identify and understand their blind spots proactively. A common practice materiality assessment asked both internal and external stakeholders to rank issues according to how significant they thought the issue was – and then aggregated the internal stakeholders’ perception into a financial materiality dimension and external stakeholders’ perception into the impact materiality dimension.

“From a sustainability point of view, a perception-based approach to sustainability materiality is heavily flawed. It relegates the concept of materiality to being a popularity contest, where deciding which stakeholders to involve to which degree is the main vector influencing the outcomes. With materiality’s origins as a financial accounting term, it has gone unnoticed for far too long how inadequate a perception-based approach to impact materiality is. After all, which topics are most material in terms of negative impacts on people and environment should not be defined by which impacts are most perceivable by stakeholders but, well, by the actual impact.”

Fact-based materiality at the heart of ESRS

In today’s debate around corporate sustainability, it has been widely acknowledged that the ESRS will firmly place double materiality at the heart of the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). What went largely unnoticed and arguably underappreciated, is that ESRS is challenging the previous mental model around perception-based materiality. In its general principles, it states that “sustainability matter is material from an impact perspective if it is connected to actual or potential significant impacts by the undertaking on people or the environment over the short-, medium- or long-term”. Sure, involving stakeholders to identify impacts is still a good way to make different voices heard, but notice: Not what’s perceived to matter matters, but actual impact.

In terms of working with sustainability practically, this mental model shift makes a world of a difference. As we have supported multiple clients with ESRS-based materiality assessments, we can witness a transformational power unfolding: Corporate sustainability is moving away from being a “journey” with shifting goalposts and definitions, and towards commonly shared and end-goal-focused strategies based on the best available science (such as planetary boundaries). Whether companies are required to disclose and address negative impacts is no longer dependent on a customer willing to vote with their wallet or an investor being on top of the agenda. Instead, a thorough mapping of impacts along the value chain lays the foundation for understanding the systemic connection between strategy, business model and our challenge of meeting everyone’s needs within our planetary boundaries.

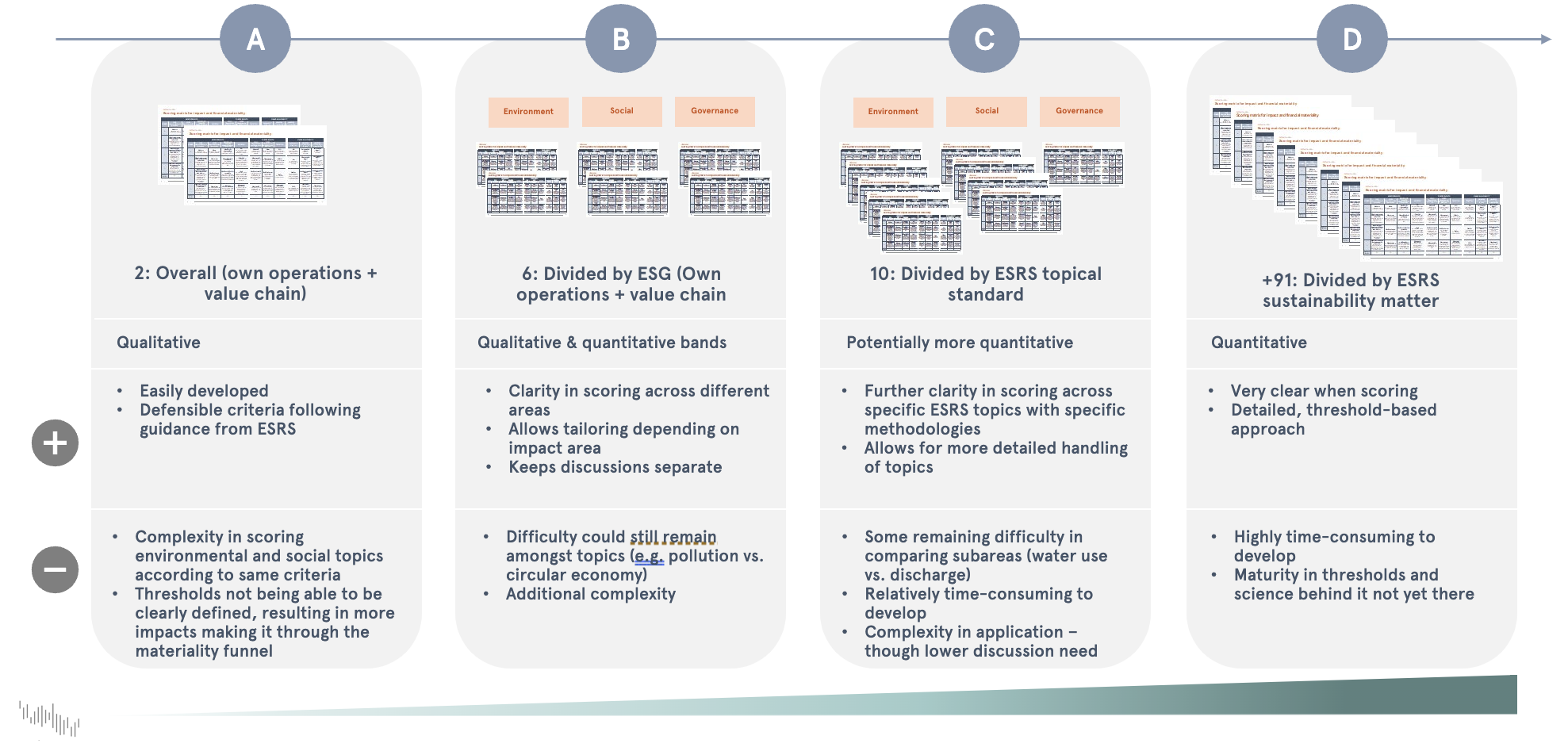

Next up, double materiality needs to undergo an evolution to sharpen definitions and methodologies. In a collaborative approach, topical experts, standard-setters, and corporate sustainability professionals should work together to flesh out in detail which level of impact is in line with our planetary boundaries and minimum social standards. This involves a series of incremental developments (see figure above). In a first step, companies need methodologies to assess severity and likelihood of impacts to ensure a stringent and coherent approach. Building on that, materiality methodologies could be unfolded to cover separate thresholds and contexts for different topics (e.g., emissions in line with the climate change planetary boundary), sub-topics (e.g. by ESRS disclosure requirements) and industries (taking inspiration from e.g., the Science-Based Target initiative). At Nordic Sustainability, we have embarked on this journey with our clients – and hope to be able to contribute to a coherent, stringent and (most importantly) better approach to materiality assessments going forward.